For this day, a word:

ἀγαθόκακόλόγος

Rendered in English:

agathokakological

Definition: adjective; composed of both good and evil parts.

The eleventh of November flounders in late autumn like a Navy diver swimming through the gaps in a rubber-ducky regatta. Wedged between the debauched sugar haze of Halloween and the stuffed poultry fog of Thanksgiving, Remembrance Day scrabbles for notice amidst the year-end miasma of revelry.

My choice of the European nomenclature highlights one of the differences between the United States of America and Europe — in the arithmetic of war, the Europeans have a greater tally to remember.

That cross-Atlantic death toll does not diminish American efforts to honor the sacrifices of those who modeled the sweetness and nobility inherent in dying for one’s country.1 The transition from Armistice Day, to Remembrance Day, to Veterans’ Day signaled an attempt to expand the collective sacred memory from one conflict too many. Yet since the last veterans returned from Korea, our customs earn more honor in the breach than in the keeping. We Americans have our monuments, our cemeteries, our parades, and our concerts. But for every gesture of respect and gratitude, we trump our magnanimity with indifference and hostility.

The bleak angles of the Vietnam Memorial Wall make it the most American of our memento mori, our remembrances for the dead.

It breaks ranks from the surrounding classical tchotchkes, representing American sorrow and failure, instead of majesty and triumph. So many different things shifted in the twentieth century that any attempt to catalog the extent or pace of the societal transmutations strains software and discourages thinkers. In an epoch of endless change, the Vietnam era marks a pernicious twisting of an ethos of veterancy, from honored citizens, to tolerated neighbors, to despised panhandlers and amputees.

Monuments may venerate the dead. Pensions, healthcare, therapy, and housing will succor the living.

We denizens of the twenty-first century skive the funding of museums, libraries, and monuments; we cheat our veterans out of their rightful tithes. That word, tithe, holds powerful religious connotations, but the English word ‘tithe’ springs not from any theological concept, but rather from the Old French:

tailleur

Definition: cut; both the action of cutting, and that which remains after cutting, as in cuts of meat. Cognate with the occupation of tailor, and the surname Tyler.

In spite of our technological prowess, our educational attainments, our smug claims of facile remembrance and digital memory, we forget. We forget our veterans, we forget our neighbors, we forget ourselves. We forget our principles, we erase our histories, we obliviate the better angels of our nature.2 And why should we not? Such forfeitures of recall are normal to agathokakological beings like ourselves. Natural humanity forgets, and cheats, and steals, and kills. Exchange the fancy smartphone for a flint hand ax, replace the remote control with a bone club, and the opening scene of Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey seems the eternal human condition — the behavior remains the same, but the props and sets improve.

However, commemorating the eleventh of November as a memoriam hodie demonstrates that things both public and private, res publica et privata, need not remain in a miserable state. We can stop the war. We can sign a peace. One hundred years ago today, our political ancestors decided on a more clement path. Clemency, concord, consistency, and charity still operate as possible choices in human thought and conduct. If only we would embrace those virtues with the same fervor whereby we clutch at our petty hatreds and saccharine sins.

The eleventh of November sits as the most agathokakological day in the year, a day when the best of human intentions could not grapple with the intensity of human memory, of the remembrance of things suffered. Good and evil, ever contending in all of human societies, in all people everywhere and everywhen. As Vivian Gornick noted3:

It is hard to fight an enemy who has outposts in your head.

The armistice of 11/11/1918 stopped the fighting of the First World War, but the Treaty of Versailles that followed seven months later only perpetuated the indignities and humiliations that started the whole enchilada of suffering. Twenty-one years after 11/11/1918, the unresolved tensions erupted in the Second World War and, well, you can see how things have gone on since then.

But if we can remember the horrors of the past, we can labor to prevent future calamities. Thereby we set the seal between history and holiness, and forge the link between scholarship and self-improvement. Each holds to key to the mastery of the other. And that, fair readers, is the purpose of Dicaeopolis — to move us all closer to the righteous city of the future, by a close remembering of the past.

To become engraved upon our souls, all history must be linked to the personal, to our own experiences and paradigms. 11/11/1918 holds that quality for me.

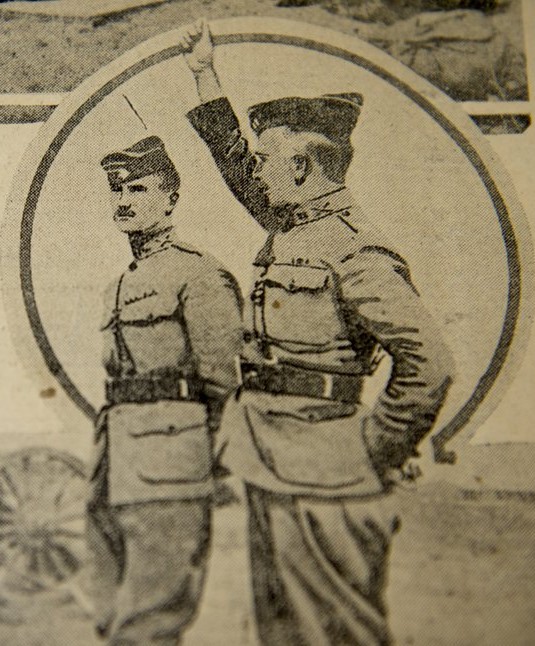

One hundred years ago today, my local newspaper published a series of photographs as part of its reporting on the armistice. The paper included the above image of my second-great-grandfather, E.G. Woolley, with his comrade-in-arms W.E. Kneass, taken in France. Great-Great-Grandpa Edwin’s expression lacks a clear emotion; does he tolerate the photographer, does express ennui at the situation, or does he look off at some other facet of the American Expeditionary Force? I cannot say for certain, only that his captured gaze seems to assay my soul.

“What are you doing with yourself, you pompous twit? How will you reckon my deeds of heroism and bravery, to say nothing of my perched cap and cinched belt? Who are you, sir? Do you descend from me in spirit and will, as well as blood?”

One day I must needs answer Edwin Gordon Woolley, Junior for the use I have made of his surname and genetic material. I pray I shall answer him well. If I provide him satisfaction, I will do so through my remembrance and application of all the valiant whom we venerate today, the sacrifices they made, the blood they shed, and the ideals they fought to preserve.

In the words of another worthy relative4:

Our greatest need is to remember

As this is written, so may this be done.

Be well,

Spencer Curtis Woolley

Notes

1. More properly, Dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori. Sometimes, but not always, a lie. Compare Wilfred Owen and Horace III.2.13

2. Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address

3. Vivian Gornick, “Woman as outsider,” in Women in a sexist society, ed. Vivan Gornick and Barbara K. Moran (New York: Basic Books, 1971), 55. In most online sources, Sally Kempton receives attribution for this phrase. But those attributions appear from either other online sources, or collections of quotations, without any bibliographic chain back to the original citation. Gornick’s syntax appears to be the first printed rendition.

4. Spencer W. Kimball, “Circles of Exaltation,” address to Church Educational System religious educations, June 28 1968), 5.

Images

Featured Image: “Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red,” a Great War memorial debuted at the Tower of London 17 July, 2015. Designed by Tom Piper and created by Paul Cummins, it consists of 888,246 red ceramic poppies, one each for every native British or Commonwealth soldier killed in the war. Image credit here.

1. Touching the Vietnam Memorial Wall. The original uploader was Skyring at English Wikipedia. [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons. Image credit here.

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey. Directed by Stanley Kubrick. Washington, D.C.: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1968. Image credit here.

3. Jeremy Harmon, “See The Salt Lake Tribune when WWI ended 100 years ago,” The Salt Lake Tribune, November 11, 2018, https://www.sltrib.com/news/2018/11/09/see-salt-lake-tribune/. Image credit here.